Group B Streptococcus Infection Presenting as Ludwig's Angina Beyond Infancy

Ahmed Al Jabery , Salwa Al Kaabi , Aysha Al Kaabi and Hossam Al Tatari

DOI10.21767/2573-0282.100039

Ahmed Al Jabery1, Salwa Al Kaabi2*, Aysha Al Kaabi1 and Hossam Al Tatari2

1Pediatric Department, Division of General Pediatrics, Tawam Hospital, UAE

2Pediatric Department, Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Tawam Hospital, UAE

- *Corresponding Author:

- Salwa Alkaabi

Pediatric Department, Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases

Tawam Hospital, UAE

Tel: +971-501-668-845

E-mail: salsaeed@seha.ae

Received date: January 24, 2017; Accepted date: March 02, 2017; Published date: March 08, 2017

Citation: Al Jabery A, Al Kaabi S, Al Kaabi A , Al Tatari H (2017) Group B Streptococcus Infection Presenting as Ludwig's Angina Beyond Infancy. Pediatric Infect Dis 2:39. doi: 10.21767/2573-0282.100039

Abstract

Ludwig’s angina is a serious and rapidly progressive cellulitis of the floor of the mouth which involves the submandibular, sub-maxillary, and sublingual spaces of the face. It uncommonly occurs in adults and children and its early recognition is paramount. With early diagnosis, airway observation and management, aggressive intravenous antibiotic therapy, and judicious surgical intervention, this disease should resolve without any complications. Here we report a case of an immunocompetent adolescent who developed Ludwig’s Angina due to Group B Streptococcus (GBS) infection who was successfully treated with surgical intervention and antibiotics therapy. To our knowledge this is the first reported case of GBS infection beyond infancy presenting as Ludwig’s Angina in an immunocompetent adolescent. There are other reported cases in the literature of GBS infection presenting beyond infancy but none of the cases presented with Ludwig’s Angina.

Keywords

Ludwig’s angina; Pediatrics; Group B streptococcus

Abbreviations

GBS: Group B Streptococcus; LA: Ludwig’s Angina; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; CRP: C Reactive Protein; MRSA: Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcal Aureus; I&D: Incision and Drainage.

Introduction

Ludwig’s angina is a rapidly progressive and potentially life-threatening cellulitis of the submandibular spaces [1]. The mortality rate of the disease exceeded 50% in the pre-antibiotics era [2]. This rate has significantly been reduced since the 1940s with the introduction of antibiotics, the improvement of oral and dental hygiene, and the aggressive surgical approaches [3]. Because Ludwig’s angina has become uncommon in adults and children, many physicians have limited experience of it.

The German physician Wilhelm Frederick von Ludwig was the first to describe this infection in 1836 as a rapidly progressive gangrenous cellulitis and edema of soft tissues of the neck, floor of the mouth. The feared complications of this disease includes; airway obstruction which is the main cause of mortality [4]. The diagnosis of this condition is based on clinical criteria proposed by Grodinsky [4] which include:

• Bilateral infection in more than one compartment of the submandibular space.

• Gangrenous serosanguinous infiltrate with or without pus.

• Involvement of connective tissue fascia and muscle but not glandular structures.

• Spread by continuity rather than by the lymphatics.

Most of the reported cases are due to infected lower molars, most commonly the second or third molar [5]. The causative organisms are typically polymicrobial, comprised of the oral bio flora [5]. Patients classically present with fever, malaise, sudden onset of tender swelling of the floor of the mouth, associated with dysphagia, dyspnea, and drooling. The fact that some patients may present with trismus can delay diagnosis and initiation of therapy [5]. Physicians should be vigilant regarding impending respiratory distress and the threshold for intubating such patients should be low [5]. Empiric antibiotics therapy should be promptly initiated to cover for beta-lactamase anaerobic, aerobic organisms and Staphylococcus aureus in immunocompetent patients. Anti-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcous aureus should be considered in high risk population [6]. Complications other than airway compromise include spread into the parapharyngeal space and the thoracic cavity causing mediastinitis, empyema or even lung abscess [7].

Here, we report a case of Ludwig’s angina in a 12-year-old immunocompetent boy due to GBS. We believe this is the first case report of this infection due to GBS.

Case Description

A previously healthy 12-year-old Emirati male, presented to the Pediatrics emergency department with a chief complaint of right lower facial swelling of two days’ duration. The swelling involved the right mandible and the submandibular area. The patient reported waking up due to severe toothache involving the right lower molar, and that is when he first noticed the swelling that has been increasing ever since. He also complained of difficulty opening his mouth which limited his oral intake. However, his breathing was not affected. A month ago, he underwent pulpectomy of his lingual 46th molar.

On presentation his temperature was 36.8C with a pulse rate of 90 beats per minute, and a respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute with an oxygen saturation of 100% on room air. The patient was seen laying down with his mouth open and drooling. On physical examination, mouth opening was limited to approximately 4 cm (interincisal distance) with an elevation of the floor of the mouth evident upon tongue elevation. A submandibular swelling appreciated which was indurated, non-fluctuant, erythematous, warm and severely tender to touch. His tongue was non-inflamed and non-tender. “Figure 1”.

Laboratory workups were all within normal limits except for an elevated CRP (116 mg/L). Patient was admitted with a preliminary diagnosis of dental abscess with extension to the deep neck tissue, and was placed on IV Amoxicillin/Clavulinic acid 25 mg/kg/dose TID and oral paracetamol PRN. Vitals were set to be monitored q 4 h. Ultrasound of the neck revealed: soft tissue edema of the neck, few bilateral cervical and submandibular lymph nodes noted with the largest being 9 mm. After infectious disease consultation, a diagnosis of Ludwig’s Angina was considered and the patient was switched to IV Clindamycin 10 mg/kg/dose q 6 h to provide better anaerobic coverage and MRSA (methicillin resistant Staphylococcal aureus) coverage. Maxillofacial surgeons assessed the patient and decided that the patient should be managed with parenteral antibiotics and surgical intervention is not needed as the airway was not compromised.

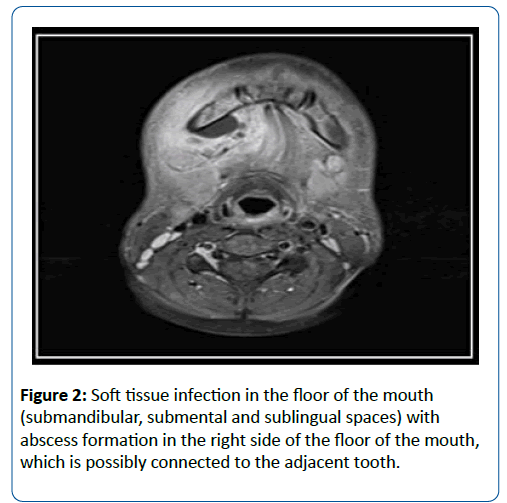

After 4 days of clindamycin the patient condition remained static without any clinical improvement so MRI of the neck was recommended at that stage to rule out any collection. Neck MRI reported soft tissue infection in the floor of the mouth, submandibular, sub mental and sublingual spaces with abscess formation in the right side of the floor of the mouth which is possibly connected to the adjacent tooth, Findings in keeping with Ludwig’s angina “Figure 2”.

Due to lack of clinical improvement on parenteral antibiotic and the presence of abscess as reported by the MRI, maxillofacial team evaluated the patient again and decided to proceed with incision and drainage with dental extraction, although the airway remained patent throughout the illness.

Culture grew GBS that is susceptible to clindamycin. Patient showed significant improvement after the surgery and was discharged on clindamycin 10 mg/kg/dose TID for ten more days. Repeated inflammatory markers prior to discharge were trending down. The patient was doing great with complete resolution of his symptoms when he was seen in the clinic after one week of discharge.

On the next day the patient underwent I&D and dental extraction. Culture grew GBS that is susceptible to clindamycin. Patient showed significant improvement after the surgery and was discharged on clindamycin 10 mg/kg/dose TID for ten more days. Repeated inflammatory markers prior to discharge were trending down. The patient was doing great with complete resolution of his symptoms when he was seen in follow up a week later.

Discussion

Despite the use of antibiotics, submandibular and sublingual infections can progress to Ludwig's angina in few hours [5]. Therefore, every periodontal infection and infections of the floor of the mouth should be treated immediately to avoid progression to fatal Ludwig's angina.

In children, 50% of Ludwig’s angina cases have an odontogenic etiology, whereas 70-90% of adult cases are odontogenic [8,9]. Bacterial culture isolates from patients with Ludwig’s Angina with abscess formation usually have both aerobic (e.g., b-hemolytic streptococci, staphylococci) and anaerobic species. Gram- negative bacteria, such as Neisseria catarrhalis, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Haemophilus influenzae, have also been reported [6]. Our patient grew GBS which to our knowledge has never been reported before in the medical literature.

Patients with Ludwig’s angina usually present with focal and systemic signs and symptoms. Focal symptoms can include tongue and tooth pain, throat pain, dysphagia, trismus, dysphonia, and drooling, and are often accompanied by local physical examination findings such as progressive bilateral submandibular and submental neck swelling, firm induration of the floor of the mouth, and edematous posterior and superior displacement of the tongue (e.g., protrusion or elevation) [10]. Patients are often sick looking with systemic signs and symptoms including fever, chills, malaise, and dehydration. More serious findings such as dyspnea, cyanosis, stridor, and tongue displacement imply an impending airway crisis [11]. Pediatricians must be vigilant since early signs and symptoms of obstruction might be so subtle which could delay initiation of proper medical therapy and timely consultation for emergency and surgical treatment. In the early 1900s, airway compromise was the leading cause of death, at which time, 67% of patients with Ludwig’s angina required anticipatory or emergent intubation [11]. Since 1943, antimicrobial therapy has reduced the frequency of airway intervention to <50% [12].

Complications of Ludwig’s angina include sepsis, pneumonia, asphyxia, empyema, pericarditis, mediastinitis, and pneumothorax [7]. The mortality rate from Ludwig’s angina is currently 10-17% in the pediatric population [13]. Careful assessment and observation of the airway is paramount since there is a recent trend of reluctance for immediate airway intervention [13].

Early and aggressive antibiotic therapy must aim to cover both aerobes and anaerobes. Penicillin or a penicillin derivative, with additional anaerobic coverage with clindamycin or metronidazole, is frequently used [3]. Some experts believe that intravenous steroids decrease edema and cellulitis, which helps maintain airway integrity, improves antibiotic penetration into the infected area, and reduces the length of hospital stay [6]. Surgical decompression is indicated in case of poor response to medical therapy or in patients who show clinical evidence of localized abscess formation upon initial physical examination [7]. Contrast-enhanced CT imaging should be considered to assess the extent of the abscess and detect possible odontogenic etiology [14]. To minimize radiation exposure, MRI is also often used as an alternative in pediatiatric population. If a dental infectious source or involvement of the parapharyngeal, retropharyngeal, or mediastinal space is noted, immediate consultation with the relevant surgical services is indicated.

Conclusion

Ludwig’s Angina is an uncommon but potentially fatal sub-mandibular cellulitis. To our knowledge this is the first reported case of GBS infection beyond infancy presenting as Ludwig’s Angina in an immunocompetent adolescent. There are other reported cases in the literature of GBS infection presenting beyond infancy but none of those cases presented with Ludwig’s Angina. Although modern medical and surgical interventions for Ludwig’s angina have improved outcomes, it remains a potentially lethal disease in the pediatric population. Early recognition of the disease is paramount. Pediatricians and physicians should consider Ludwig’s angina when patients present with symptoms such as recent oral cavity and neck swelling. With early diagnosis, airway observation and management, aggressive intravenous antibiotic therapy, and judicious surgical intervention, this disease should resolve without any complications.

References

- Burke J (1939) Angina ludovici: a translation, together with biography of Wilhelm F.V. Ludwig. Bull Hist Med 7:1115e1126.

- Williams AC (1940) Ludwig’s angina. Surg Gynecol Obstet 70:140e149.

- Patterson HC, Kelly JH, Strome M (1982) Ludwig’s angina: an update. Laryngoscope 92:370e377.

- Barakate MS, Jensen MJ, Hemli JM, Graham AR (2001) Ludwig's angina: report of a case and review of management issues. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 110: 453-456.

- David M, Lemonick DM (2002) Ludwig’s Angina: Diagnosis and Treatment. Hospital Physician 38: 31-37.

- Busch RF, Shah D (1997) Ludwig’s angina: improved treatment. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg117:S172eS175.

- Britt JC, Josephson GD, Gross CW (2000) Ludwig’s angina in the pediatric population: report of a case and review of the literature.Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 52:79e87.

- Srirompotong S, Art-Smart T (2003) Ludwig’s angina: a clinical review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 260: 401-403.

- Sethi D, Stanley R (1994) Deep neck abscesses-changing trends. J Laryngol Otol 108: 138-143.

- Finch RG, Snider GE, Sprinkle PM (1980) Ludwig’s angina. JAMA 243: 1171e1173.

- Har-El G, Aroesty JH, Shaha A, (1994) Changing trends in deep neck abscess. A retrospective study of 110 patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral RadiolEndod. 77:446e450.

- Moreland LW, Corey J, McKenzie R (19880 Ludwig’s angina. Report of a case and review of the literature. Arch Intern Med 148:461e466.

- KurienM, Mathew J, Job A, Zachariah N (1997) Ludwig’s angina. ClinOtolaryngol Allied Sci 22:263e265.

- Parhiscar A, Har-El G (2001) Deep neck abscess: a retrospective review of 210 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 110:1051e1054.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences